About

What We Do

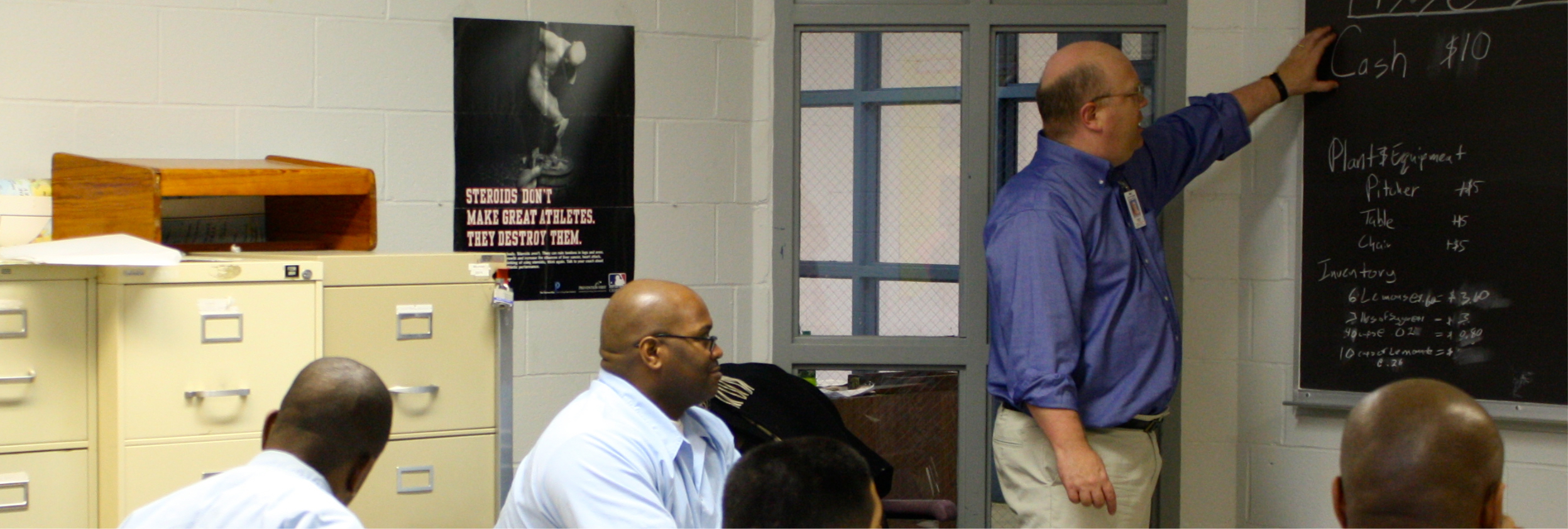

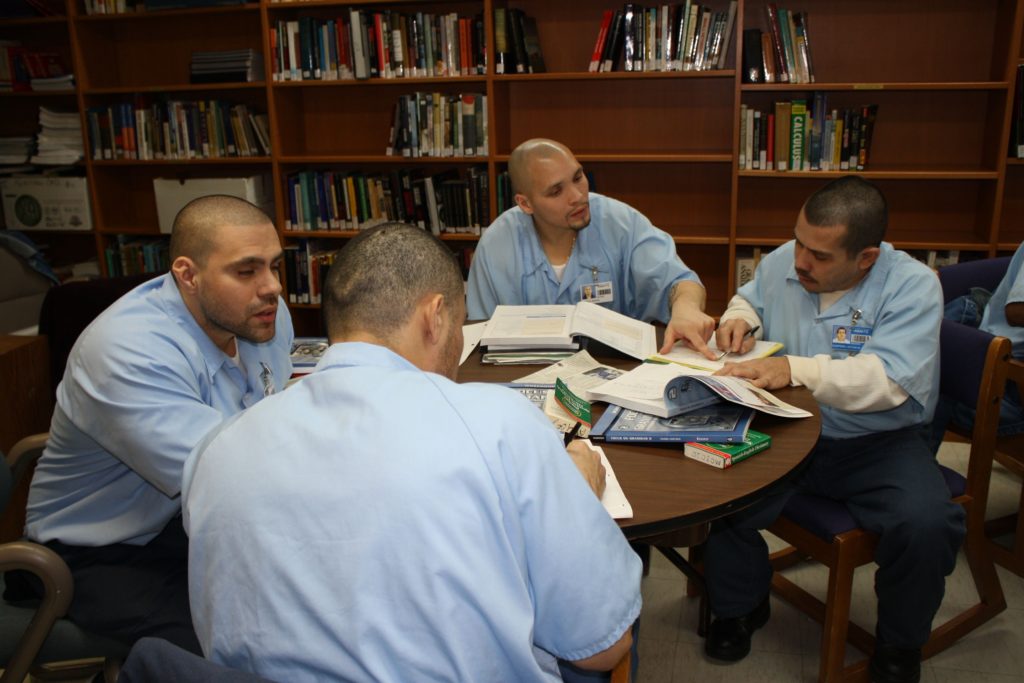

EJP is a comprehensive college-in-prison program based at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. We offer programming in three areas.

First, we offer upper-division University of Illinois courses and extracurricular activities at Danville Correctional Center, a medium-security men’s prison about 45 miles from the Urbana-Champaign campus. The learning community that EJP instructors and students continually recreate at the prison is at the core of everything else that EJP does, and drives our other activities.

Second, through our Reentry Guide Initiative, we produce reentry guides and other reentry resources, and distribute them to incarcerated individuals, family members, and service agencies across the state and beyond.

Finally, we host programs on campus to meet some of the needs that we have become aware of through our work. For instance, in recognition of the deleterious impacts of incarceration on family members, we have a scholarship program. To support informed policy-making around criminal justice, we host events on campus and the community to educate the public and elected officials.

EJP is based at a top research university, in its highly-ranked College of Education. Because we take scholarship seriously, EJP runs a research group, produces resources for other higher education in prison programs, and supports EJP members in producing critical scholarship about prison education, as well as creative works.

We are committed to building an open, safe, gentle, inclusive learning environment within EJP. We believe that a rigorous and critical education program requires the cultivation of such an environment and that self-reflection is an important part of creating and sustaining such an environment. Our Diversity and Inclusion Commitment guides our activities in this regard.

Organization

The mission of the Education Justice Project is to build a model college in prison program that demonstrates the positive effects of higher education on incarcerated students, their families, the communities to which they return, the host institution, and society as a whole.

Our vision is a more humane and just society, sustained through education and critical awareness.

Since 2011, the Education Justice Project has been a unit of the Department of Education Policy, Organization, and Leadership (EPOL). We aim to become a campus center in the coming year.

With only five full-time staff, we rely greatly on the energy and dedication of dozens of EJP volunteer members—graduate and undergraduate students, faculty, staff, and community members. Their in-kind contributions amount to many hundreds of hours each year. Working collaboratively, they help to design and implement programs and EJP outreach activities.

EJP has about 100 active outside (i.e. non-incarcerated) members during any given semester and about 70 incarcerated students. What we term the “EJP universe” is much larger, though, and consists of almost 500 former EJP instructors (“faculty affiliates”), program alumni (released students), and students who have been transferred to other prisons.

The EJP Handbook provides an overview of EJP’s history, mission, and policies. It also includes a list of all courses and programs EJP has offered to date.

Prison Abolition

EJP would not exist but for the hard and painful reality that our society incarcerates individuals. EJP, through our programs and activities, seeks to mitigate the impacts of incarceration today and to create conditions that support the creation of more humane and just responses to harm and violence.

The fact that we do these things by necessarily engaging with a system that many (not all) EJP members find abhorrent creates a tension that runs through just about everything we do.

How do we ensure that EJP partners effectively with prison staff and administrators, creating smooth-running programs that become part of the day-to-day at Danville Correctional Center, without becoming part of the prison apparatus? How do we argue for expansion of higher education in prisons across the state, while at the same time insisting on the need to close prisons?

What does an abolitionist reentry guide look like? Or an abolitionist college-in-prison program? What would it look like for our host institution, the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, to enact abolitionist values?

We are committed to continued interrogation of these and similar queries, in a spirit of inclusion and critical reflection.